Our country has long excluded people of color from accessing the power of the horse

Art by Tess Whitfort. (Used with permission)

The image was striking: a young black woman riding an enormous horse through the Oakland protests, fist raised above her head. It was bold, powerful—and uncommon, as the equestrian world is heavily white.

“There has to be a change in horse sports. This cannot be so white,” Brianna Noble, the protester in the image, told Heels Down magazine. “As a black person who rides, I experience some of the blatantly racist stuff and then I get those who just won’t acknowledge me, won’t look me in the eye. And I’m an adult. There are kids out there who stop riding because of racial pressure and the hostile environment it causes. Race is this awkward thing that people don’t really talk about. And the silence is stifling.” (See the photo and read the article here.)

Equine sports are exorbitantly expensive. So it would be easy to explain away racial disparities as a simple matter of financial barriers. If people of color in this country have less wealth than white people, of course it follows that fewer people of color can afford to participate in a costly industry—one that, by the way, is not just about entertainment but includes activities that build confidence, work ethic, and responsibility; and offers therapies for numerous physical and mental health issues. The economic disparity is problematic, but surely no one is against the involvement of people of color if they can afford it, right?

I’m not a person of color and am quite open about the fact that my knowledge of horses is on the intellectual/historical side rather than on the practical side. I’m not the right person to speak with authority on the ways in which racism manifests in the horse industry today. There are many other people, including Brianna Noble, who have much to say on that subject.

But having spent the last few years studying and writing about how the horse shaped U.S. history, I can tell you with certainty: you can’t follow the thread of the horse without encountering the history of systemic racism surrounding it. Today’s barriers to the horse industry extend far beyond cost alone.

Art by Maria Elena Serratos. (Used with permission)

The story line of much of our country’s early development is simple: whoever wielded the horse most effectively won, whether victory meant land, money, status, or all three. First, the Spanish reintroduced the horse as a weapon to conquer the Americas. They recognized the horse’s power and clung tightly to it, initially banning the native peoples they encountered from riding. But the greatest source of Spanish strength became their own downfall when the native peoples of the Great Plains did access these horses—and learned to employ them much more effectively than the Spanish ever had.

This power shift arguably cost the Spanish North America. Maddeningly for the would-be colonizers, these Horse Nations managed to relentlessly beat back white encroachment into much of the plains for nearly 200 years.

And then. It was as if the whole country seemed to take note at the same moment that horses meant dominance. The attacks came from every angle on people of color who had gained power or status in some way through horses. In the late 1800s, the government realized it would only be able to remove the Horse Nations from the Great Plains—the last swath of uncontrolled U.S. soil at that time—by “relieving them” of the source of their incredible strength: their horses. Any excuse to “relieve” the horses from the indigenous people of the East was a good one, too. (The forced relocation process known as the Trail of Tears alone stripped these nations of thousands of their horses.)

Meanwhile, the racing industry began to erase the legacy of famed black jockeys from its history after segregationist laws essentially banned them from the sport in the early 1900s. (Some of these jockeys had survived enslavement prior to the Civil War and then risen to celebrity status in the industry.) And an emerging genre of literature, the western, wrote the one-fourth of cowboys who were black right out of the history of the West, portraying the scene as almost exclusively white.

In short, white Europeans first controlled access to the modern horse in what would become the U.S. As the horse became more ubiquitous, some people of color were able to draw power from it. However, through the forces just described, alongside other facets of systemic racism that have plagued the U.S., white Americans eventually reclaimed the horse quite forcefully for their own.

All that is to say, labeling the issue of racial disparities in the horse industry today as a matter of finances, while troubling enough, is a gross simplification that denies centuries of U.S. history.

Access to and mastery of horses no longer equates to dominance in the same ways it did a few hundred years ago. But that’s not an excuse to accept that people of color have a long history of exclusion from the benefits horses still offer. For one thing, in a $50-billion-per-year industry, there’s a lot of money to be made for those who rise to the top. Perhaps more importantly, horsemanship skills and horse-human relationships empower youth and adults by boosting confidence and teaching work ethic and responsibility. Many types of equine-assisted activities and therapies address physical and emotional issues, as well.

Brianna Noble is channeling the national attention she received from her protest ride on her horse, Dapper Dan, to follow her dream of launching a program for people historically excluded from accessing horses: “Humble, a project with the mission of exposing underprivileged and marginalized communities to the horse world, fosters respect, confidence, and accountability for urban youth through equine experiential learning.” I hope you’ll read about Humble and consider making a donation to help get the program off the ground.

The organizations below also seek to empower young people of color and at-risk communities by supporting them in learning horsemanship skills and participating in equine-assisted activities and therapies. I hope you’ll consider joining me in reading about their work, amplifying their messages, and, if possible, donating to their programs. And please send me more organizations to add to the list!

Ebony Horsewomen

Saddle Up and Read

Compton Jr. Equestrians

Urban Saddles

CBC Therapeutic Horseback Riding Academy

CORRAL Riding Academy

Sage to Saddle

Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club

Philadelphia Urban Riding Academy

And here’s a podcast of interest, too:

Young Black Equestrians Podcast

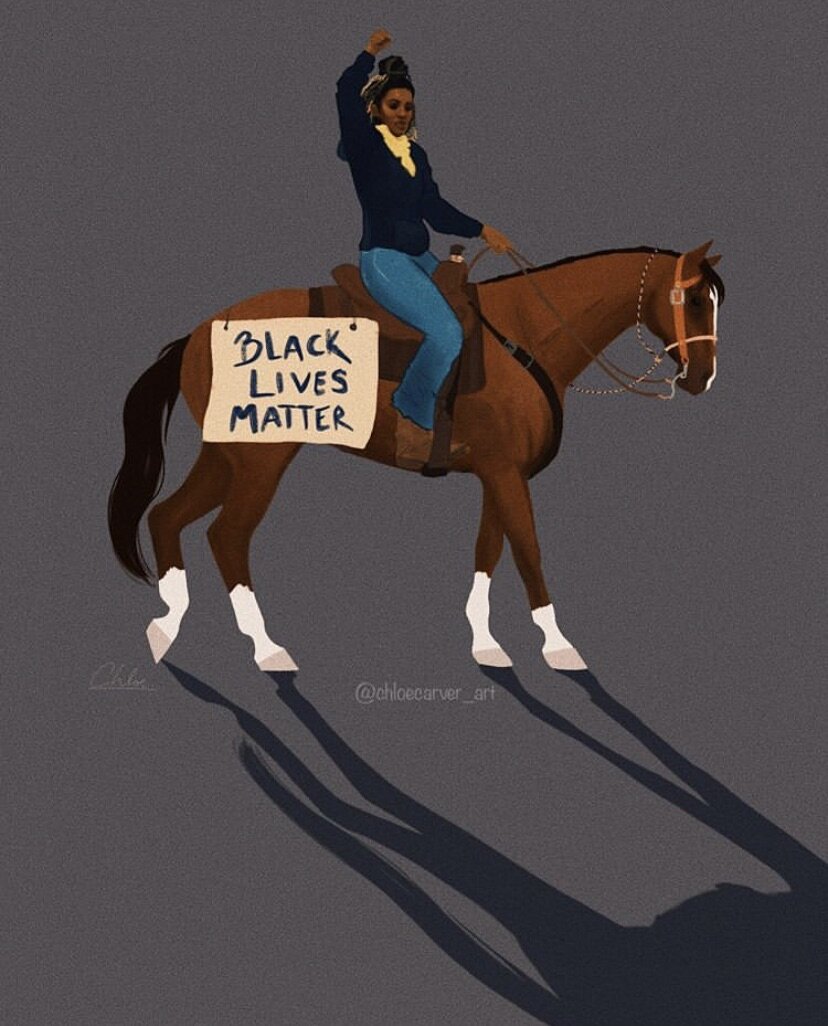

Art by Chloe Carver. (Used with permission.)

Art by Cristina Ibarra. (Used with permission)